COOKS LANDING - One recent morning, David Sohappy Jr. steered his small boat out onto the Columbia River to check fishing nets in the place three decades ago he became ensnared in "Salmonscam," federal undercover fish-buying sting that would eventually garner national attention.

As he turned off the boat's engine, his brother, Andy Sohappy, 57, and nephew Kyle Brisbois, 20, reached into the frigid waters to pull in nets containing a handful of sturgeon and two salmon.

"It's a little slow right now - the run is a little late," Sohappy Jr., 58, said.

The trio were exercising their fishing rights reserved under the 1855 treaty with the federal government, rights they say Salmonscam trampled on.

Sohappy Jr. and his father, the late David Sohappy Sr., and three other Yakama tribal members - Wilbur Slockish Jr., Leroy Yocash and Matt McConville - were convicted in U.S. District Court in April 1983 for selling salmon caught out of season to undercover federal agents.

Not long afterward, they where charged in their own tribal court for violating tribal fishing regulations in the same incident.

The fishermen contended they were exercising their traditional fishing rights established by their Seven Drum religion since time immemorial and protected under the treaty.

For six years, the saga played out. Slockish and Yocash went into hiding at one point and the Yakama Nation's Tribal Court was caught in a jurisdictional standoff with the federal court that culminated with a tribal jury acquitting the five fishermen, although they still received harsh sentences from the federal court.

This month marks the 30th anniversary of the final tribal court case and Yakama tribal officials are holding two events this week - a Tuesday presentation of the case at Heritage University and a Friday river walk at Columbia Hills State Park about 25 miles southwest of Goldendale along the Columbia River.

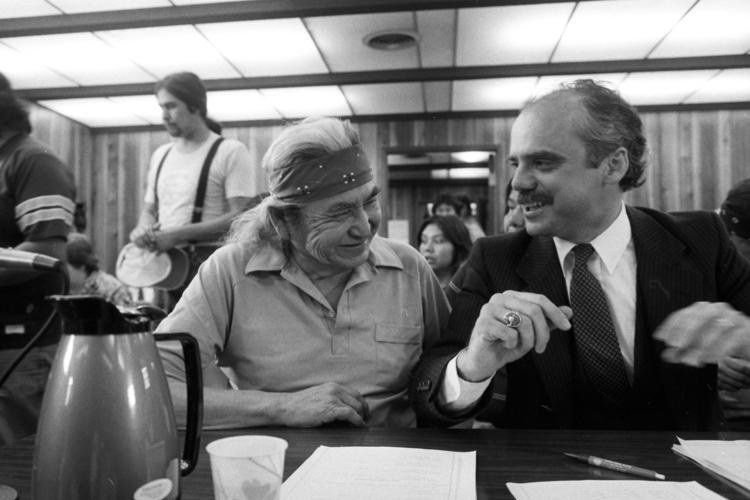

At the Tuesday event, attorney Tom Keefe will share his experience defending the men in tribal court.

"I'm happy the younger generation right now is interested in this side of the story," Keefe said. "I think I have an obligation to David (Sohappy Sr.) to go there and tell people what he said, what he stood for and what I've learned."

A religious matter

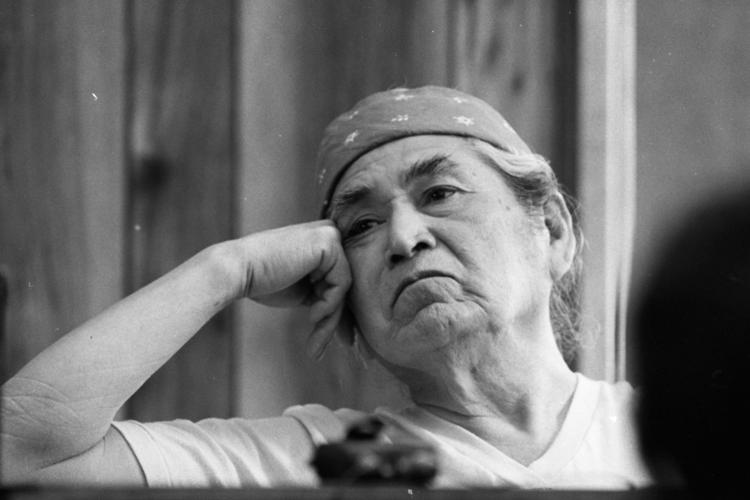

A Wanapum religious leader, David Sohappy Sr. strongly held his ties to the river and his aboriginal fishing rights.

Under his belief, he and his people were given the salmon to survive, and were allowed to fish six days a week, with Sunday off to assure salmon wouldn't be over-fished.

Photos: David Sohappy, Jr.

David Sohappy Jr., 58, left, and his brother, Andy Sohappy, 57, right, boat out to check their fishing nets on the Columbia River near Cook, Wash., Friday, April 20, 2017. Sohappy Jr. and his dad along with three other Yakama tribal members were convicted in U.S. District court in 1983 for selling salmon caught out of season to undercover agents. The sting is known as Salmonscam. The case was argued both in federal and tribal court. This year marks the 30th anniversary of the tribal court case, where Sohappy was allowed to voice his side of the story. (SOFIA JARAMILLO/Yakima Herald-Republic)

The Wanapums are one of the 14 tribes confederated under the Yakama Nation.

"The Indians were the ones that depended on fish for survival," Sohappy Jr. said last week as he climbed out of his boat. "We were here first, I don't care what anybody says. We have a right to trade and barter fish. I still believe that to this day."

But federal and state authorities often didn't see it that way. They resented the elder Sohappy for his success in advocating for treaty fishing rights, said Keefe, who described the elder Sohappy as a simple 19th century man caught in 20th century political bureaucracy.

Tired of getting his nets and fish confiscated by state authorities, Sohappy took his fight to federal court where a ruling in Sohappy v. Smith established that tribes would get a fair share of fish runs. That ruling played pivotal in the landmark 1974 Boldt decision, which allocated half the annual catch to Northwestern tribes.

Those rulings touched enormous animosity on the river, Keefe said.

"It caused tremendous political fallout," he said. "There were people getting shot at in their boats, politicians were scrambling; it was just a mess."

Keefe believes the sting was an effort to target Sohappy and erode treaty fishing rights.

He said fish regulators on the river long considered the Sohappys renegades, and that state and federal authorities worked together to pull off the sting that eventually landed the fishermen in prison.

"Here's the feds who have a trust obligation to the tribe working with the jurisdictions that have harassed tribes for years," he said.

Holding to traditional fishing practices, the Sohappys even drew the ire of their own tribal council for not abiding by new fishing regulations set by the tribal government and the newly formed Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, which coordinates fisheries on the river among the Yakama, Nez Perce, Warm Springs and Umatilla tribes.

"They should never have been charged," Keefe said. "David was a charismatic villain for the state ever since Sohappy v. Smith, and a villain for tribal officials."

Federal prosecutors portrayed Sohappy Sr. as the ring leader of a years-long illegal fishing scheme, accusing him and several other Native Americans of poaching some 40,000 fish. It was later discovered the fish weren't missing. Rather, they were held up by large amounts of fluoride discharged into the river by an aluminum plant in The Dalles, Ore.

In the end, the elder Sohappy was found to have sold 317 fish worth less than $10,000 to undercover agents, while his son was convicted for selling 28 fish.

Both men were sentenced to five years in prison, while Slockish Jr. received three years, Yocash two years, and McConville one year.

Looking back at how heavily armed federal agents raided Sohappy's small dirt-floor home with a door made of driftwood, Keefe characterized the event as "the United States of America going after a flea with an elephant gun."

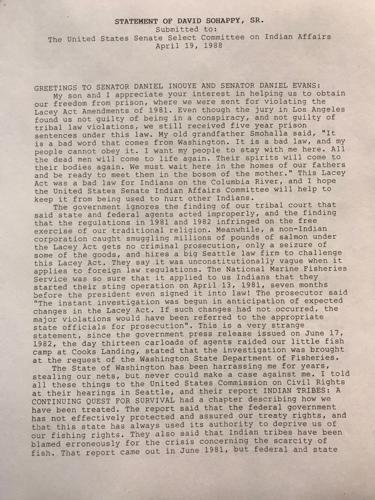

Keefe largely blames former U.S. Sen. Slade Gorton for the sting. Gorton aggressively challenged tribal treaty fishing rights earlier when he was Washington's Attorney General and as senator supported amendments to a federal act making illegal interstate commerce a federal crime. The Sohappys, who lived and fished at Cooks Landing in Washington, sold their catch across the river in Celilo Village, Ore., a well-known tribal trading hub.

And the amendments to the Lacy Act dealing with interstate commerce didn't take effect until after the buying sting that occurred between the fall of 1981 and the spring of 1982, but they were still prosecuted under it, Keefe said.

"What happened to old man Sohappy and those other Indian people really pisses me off," he said. "(Gorton) was able to federalize the anti-Indian sentiments that had existed in the state of Washington since day one of statehood. It was an absolute disgrace what they did."

Tradition on Trial

A day before the five fisherman were scheduled report to federal prison in Lompoc, Calif., to serve their sentences, tribal police arrested them for violating tribal fishing regulations. A tribal judge released them telling the five not to leave the 1.3-million-acre reservation while their case was pending in tribal court.

Two days later, a federal judge issued an arrest warrant for the five for not showing up at Lompoc.

Meanwhile, tribal prosecutors moved to have the federal warrant suspended, arguing the men should be tried by their peers in tribal court. The tribe refused to release the men to federal authorities, and a special tribal prosecutor requested the five be placed in tribal jail to avoid being whisked away by U.S. Marshals.

The Sohappys turned themselves in while the other three fishermen remained at large.

But in a surprise move a week later, tribal Judge David Ward dismissed the case, saying the tribe's two-year statute of limitations had expired before charges were brought to tribal court.

Subsequently, tribal police handed over the Sohappys and McConville to federal authorities while Slockish and Yocash remained at large.

The three fisherman were moved through five different jails or prisons before landing in Sandstone, Minn. But then Ward's decision was overturned and tribal court began seeking the return of the three men. Eventually, the federal court released them back to tribal court. Yocash was arrested without incident less than a month later while Slockish turned himself in to tribal police.

By this time the case had taken a national spotlight and brought international fame to the elder Sohappy as a beacon for tribal fishing rights. "Free David Sohappy" slogans dotted bumper stickers and T-shirts across the country.

Vigils were held outside tribal headquarters during a 16-day trial, the longest in the tribal court's history. Singers Jackson Browne and Bonnie Raitt headlined a sellout benefit for the Sohappy defense fund.

Keefe labeled his defense "Tradition on Trial" and successfully argued that the mens' traditional fishing practices trumped the tribe's fishing regulations.

But they still had to serve their federal sentences. Sixty-two-year-old Sohappy Sr. suffered a stroke in prison. His son recalled being incarcerated with serious offenders, including a murderer who found it strange they were imprisoned on fishing charges.

"A lot of guys couldn't believe it," he said. "They called us the fish mafia. 'Back away from the fish mafia, the fish killers.'"

Sohappy Jr. remembers McConville joking with inmates "Haven't you ever heard of the Apple Dumpling Gang, punk," referring to the 1975 western comedy about three orphaned children sent to live with a gambler.

But prison was hard on his dad, Sohappy Jr. said.

"He'd get his spirits up when they'd say we're going home, pretty soon they'd just knock him down, boom," he said. "But he was an older man; he was like an oak (tree). Back then I was like a willow, I could bend to their ways. I think that's what led to his stroke. I'd see him pounding on the wall, I knew he was mad."

He was placed in the same cell with his dad. "Which was good so I could take car of him," he said. "I said 'Dad, I know you're mad.' I could tell. He was grinding his teeth at night. It was hard."

Eventually U.S. Sen. Dan Inouye, then-chairman of the Special Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, intervened, saying the sentences were too harsh for the crime.

They were released after serving about 20 months.

Keefe regards Sohappy Sr. as "the Martin Luther King of tribal fishing rights in the northwest."

"He was just fiercely committed to the principals he was raised with and believed in," Keefe said. "He was by no doubt the most famous member of the Yakama Nation in history. He did become an international symbol of resistance."

* Reporter Phil Ferolito can be reached at 509-577-7749 or pferolito@yakimaherald.com. Follow him on Twitter at philipferolito@twitter.com

(0) comments

Comments are now closed on this article.

Comments can only be made on article within the first 3 days of publication.